Back to basics - SQL joins

This tutorial uses Oracle SQL syntax but the concepts are universal.

Joins are the heart of relational databases — they let you combine information stored in different tables into one coherent result. Instead of keeping everything in a single massive table, databases split data into logical chunks (like customers, orders, or products), and joins are how you connect those pieces back together to answer real-world questions. Whether you’re pulling reports, exploring relationships, or building analytics pipelines, mastering joins is what turns raw tables into insight.

INNER JOIN with common key column name

Let’s start with a simple example. Create two sample tables:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

CREATE TABLE left_table

(

id NUMBER(10) NOT NULL,

left_val VARCHAR2(50),

CONSTRAINT left_table_pk PRIMARY KEY (id)

);

INSERT INTO left_table VALUES (1, 'LEFT 1');

INSERT INTO left_table VALUES (2, 'LEFT 2');

INSERT INTO left_table VALUES (3, 'LEFT 3');

INSERT INTO left_table VALUES (4, 'LEFT 4');

SELECT *

FROM left_table;

Output:

| ID | LEFT_VAL |

|---|---|

| 1 | LEFT 1 |

| 2 | LEFT 2 |

| 3 | LEFT 3 |

| 4 | LEFT 4 |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

CREATE TABLE right_table

(

id NUMBER(10) NOT NULL,

right_val VARCHAR2(50),

CONSTRAINT right_table_pk PRIMARY KEY (id)

);

INSERT INTO right_table VALUES (1, 'RIGHT 1');

INSERT INTO right_table VALUES (4, 'RIGHT 4');

INSERT INTO right_table VALUES (5, 'RIGHT 5');

INSERT INTO right_table VALUES (6, 'RIGHT 6');

SELECT *

FROM right_table;

Output:

| ID | RIGHT_VAL |

|---|---|

| 1 | RIGHT 1 |

| 4 | RIGHT 4 |

| 5 | RIGHT 5 |

| 6 | RIGHT 6 |

An INNER JOIN is the default type of join in SQL. It combines rows from two tables based on matching values in a common column. The result only includes rows where a match exists in both tables.

In this case, only ID 1 and 4 appear in both tables.

1

2

3

4

SELECT *

FROM left_table l

INNER JOIN right_table r

ON l.id = r.id

Output:

| ID | LEFT_VAL | ID | RIGHT_VAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LEFT 1 | 1 | RIGHT 1 |

| 4 | LEFT 4 | 4 | RIGHT 4 |

Note the use of l and r aliases – they make the query easier to read. Since both tables share a column named ID, it appears twice in the result. To tidy things up, we can select specific columns:

1

2

3

4

5

6

SELECT l.id,

left_val,

right_val

FROM left_table l

INNER JOIN right_table r

ON l.id = r.id

Output:

| ID | LEFT_VAL | RIGHT_VAL |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LEFT 1 | RIGHT 1 |

| 4 | LEFT 4 | RIGHT 4 |

Another way to write an inner join is with the USING keyword, which is handy when both tables share a column with the same name.

1

2

3

4

SELECT *

FROM left_table l

INNER JOIN right_table r

USING (id);

The USING keyword works with all standard join types — INNER JOIN, LEFT JOIN, RIGHT JOIN, and FULL OUTER JOIN.

INNER JOIN with different key column names

Let’s look at a case where the key columns have different names.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

DROP TABLE left_table;

CREATE TABLE left_table

(

left_id NUMBER(10) NOT NULL,

left_val VARCHAR2(50),

CONSTRAINT left_table_pk PRIMARY KEY (left_id)

);

INSERT INTO left_table VALUES (1, 'LEFT 1');

INSERT INTO left_table VALUES (2, 'LEFT 2');

INSERT INTO left_table VALUES (3, 'LEFT 3');

INSERT INTO left_table VALUES (4, 'LEFT 4');

SELECT *

FROM left_table;

Output:

| LEFT_ID | LEFT_VAL |

|---|---|

| 1 | LEFT 1 |

| 2 | LEFT 2 |

| 3 | LEFT 3 |

| 4 | LEFT 4 |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

DROP TABLE right_table;

CREATE TABLE right_table

(

right_id NUMBER(10) NOT NULL,

right_val VARCHAR2(50),

CONSTRAINT right_table_pk PRIMARY KEY (right_id)

);

INSERT INTO right_table VALUES (1, 'RIGHT 1');

INSERT INTO right_table VALUES (4, 'RIGHT 4');

INSERT INTO right_table VALUES (5, 'RIGHT 5');

INSERT INTO right_table VALUES (6, 'RIGHT 6');

SELECT *

FROM right_table;

Output:

| RIGHT_ID | RIGHT_VAL |

|---|---|

| 1 | RIGHT 1 |

| 4 | RIGHT 4 |

| 5 | RIGHT 5 |

| 6 | RIGHT 6 |

Now the join condition must explicitly match the two differently named columns:

1

2

3

4

SELECT *

FROM left_table l

INNER JOIN right_table r

ON l.left_id = r.right_id

Output:

| LEFT_ID | LEFT_VAL | RIGHT_ID | RIGHT_VAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LEFT 1 | 1 | RIGHT 1 |

| 4 | LEFT 4 | 4 | RIGHT 4 |

Joins aren’t limited to two tables — you can chain several together to explore more complex relationships.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

CREATE TABLE another_table

(

another_id NUMBER(10) NOT NULL,

another_val VARCHAR2(50),

CONSTRAINT another_table_pk PRIMARY KEY (another_id)

);

INSERT INTO another_table VALUES (1, 'ANOTHER 1');

INSERT INTO another_table VALUES (3, 'ANOTHER 3');

INSERT INTO another_table VALUES (5, 'ANOTHER 5');

INSERT INTO another_table VALUES (7, 'ANOTHER 7');

SELECT *

FROM another_table;

Output:

| ANOTHER_ID | ANOTHER_VAL |

|---|---|

| 1 | ANOTHER 1 |

| 3 | ANOTHER 3 |

| 5 | ANOTHER 5 |

| 7 | ANOTHER 7 |

Only ID = 1 appears in all three tables, so that’s the only record returned when joining them all:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

SELECT left_id,

left_val,

right_val,

another_val

FROM left_table l

INNER JOIN right_table r

ON l.left_id = r.right_id

INNER JOIN another_table a

ON l.left_id = a.another_id

Output:

| LEFT_ID | LEFT_VAL | RIGHT_VAL | ANOTHER_VAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LEFT 1 | RIGHT 1 | ANOTHER 1 |

Self join

A self-join is simply a table joined to itself. It’s especially useful for hierarchical or parent-child relationships, such as employees and their managers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

CREATE TABLE company

(

employee_id NUMBER(3),

employee_name VARCHAR(50),

manager_id NUMBER(3)

);

INSERT INTO company

VALUES (200, 'Mark', NULL);

INSERT INTO company

VALUES (205, 'Fred', 200);

INSERT INTO company

VALUES (207, 'Peter', 200);

INSERT INTO company

VALUES (210, 'Anna', 207);

SELECT *

FROM company;

Output:

| EMPLOYEE_ID | EMPLOYEE_NAME | MANAGER_ID |

|---|---|---|

| 200 | Mark | |

| 205 | Fred | 200 |

| 207 | Peter | 200 |

| 210 | Anna | 207 |

Using a self join, we can pair each employee with their manager’s name:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

SELECT c1.employee_id,

c1.employee_name,

c1.manager_id,

c2.employee_name AS manager_name

FROM company c1

INNER JOIN company c2

ON c1.manager_id = c2.employee_id;

Output:

| EMPLOYEE_ID | EMPLOYEE_NAME | MANAGER_ID | MANAGER_NAME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 205 | Fred | 200 | Mark |

| 207 | Peter | 200 | Mark |

| 210 | Anna | 207 | Peter |

LEFT JOIN & RIGHT JOIN

After inner joins, the next family of joins expands the result set.

A LEFT JOIN returns all records from the left table, including those without matches in the right table.

1

2

3

4

SELECT *

FROM left_table l

LEFT JOIN right_table r

ON l.left_id = r.right_id

Output:

| LEFT_ID | LEFT_VAL | RIGHT_ID | RIGHT_VAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LEFT 1 | 1 | RIGHT 1 |

| 4 | LEFT 4 | 4 | RIGHT 4 |

| 2 | LEFT 2 | ||

| 3 | LEFT 3 |

A RIGHT JOIN does the opposite — it returns all records from the right table, even those without matches in the left. Right joins are less common but work exactly the same way:

1

2

3

4

SELECT *

FROM left_table l

RIGHT JOIN right_table r

ON l.left_id = r.right_id

Output:

| LEFT_ID | LEFT_VAL | RIGHT_ID | RIGHT_VAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LEFT 1 | 1 | RIGHT 1 |

| 4 | LEFT 4 | 4 | RIGHT 4 |

| 6 | RIGHT 6 | ||

| 5 | RIGHT 5 |

FULL OUTER JOIN

A FULL OUTER JOIN combines the results of both left and right joins. It returns all records from both tables, whether or not a match exists.

1

2

3

4

SELECT *

FROM left_table l

FULL OUTER JOIN right_table r

ON l.left_id = r.right_id

Output:

| LEFT_ID | LEFT_VAL | RIGHT_ID | RIGHT_VAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LEFT 1 | 1 | RIGHT 1 |

| 4 | LEFT 4 | 4 | RIGHT 4 |

| 5 | RIGHT 5 | ||

| 6 | RIGHT 6 | ||

| 2 | LEFT 2 | ||

| 3 | LEFT 3 |

Note that the order of tables in a query matters. If we switch their order, the output is slightly different.

1

2

3

4

SELECT *

FROM right_table r

FULL OUTER JOIN left_table l

ON l.left_id = r.right_id

Output:

| RIGHT_ID | RIGHT_VAL | LEFT_ID | LEFT_VAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RIGHT 1 | 1 | LEFT 1 |

| 2 | LEFT 2 | ||

| 3 | LEFT 3 | ||

| 4 | RIGHT 4 | 4 | LEFT 4 |

| 6 | RIGHT 6 | ||

| 5 | RIGHT 5 |

Note: Some modern databases, like SQLite, don’t support FULL OUTER JOIN directly. You can emulate it using a UNION of left and right joins.

CROSS JOIN

A CROSS JOIN creates all possible combinations of rows from both tables. If one table has x rows and the other has y, the result contains x × y rows. This is also called a Cartesian product.

1

2

3

SELECT *

FROM right_table

CROSS JOIN left_table

Output:

| RIGHT_ID | RIGHT_VAL | LEFT_ID | LEFT_VAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RIGHT 1 | 1 | LEFT 1 |

| 1 | RIGHT 1 | 2 | LEFT 2 |

| 1 | RIGHT 1 | 3 | LEFT 3 |

| 1 | RIGHT 1 | 4 | LEFT 4 |

| 4 | RIGHT 4 | 1 | LEFT 1 |

| 4 | RIGHT 4 | 2 | LEFT 2 |

| 4 | RIGHT 4 | 3 | LEFT 3 |

| 4 | RIGHT 4 | 4 | LEFT 4 |

| 5 | RIGHT 5 | 1 | LEFT 1 |

| 5 | RIGHT 5 | 2 | LEFT 2 |

| 5 | RIGHT 5 | 3 | LEFT 3 |

| 5 | RIGHT 5 | 4 | LEFT 4 |

| 6 | RIGHT 6 | 1 | LEFT 1 |

| 6 | RIGHT 6 | 2 | LEFT 2 |

| 6 | RIGHT 6 | 3 | LEFT 3 |

| 6 | RIGHT 6 | 4 | LEFT 4 |

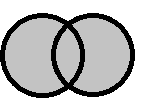

Venn diagrams & set operations

Beyond joins, SQL also supports set operations, which merge results from multiple queries rather than individual rows. Each circle in a Venn diagram represents one result set, and the shading shows which rows are included.

UNION returns all distinct records from both tables.

1

2

3

4

5

SELECT left_id

FROM left_table

UNION

SELECT right_id

FROM right_table

Output:

| LEFT_ID |

|---|

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

UNION ALL includes duplicates:

1

2

3

4

5

SELECT left_id

FROM left_table

UNION ALL

SELECT right_id

FROM right_table

Output:

| LEFT_ID |

|---|

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 1 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

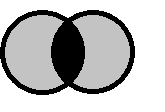

INTERSECT returns only records present in both tables.

1

2

3

4

5

SELECT left_id

FROM left_table

INTERSECT

SELECT right_id

FROM right_table

Output:

| LEFT_ID |

|---|

| 1 |

| 4 |

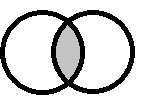

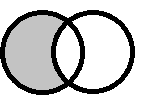

MINUS (or EXCEPT in some databases) returns rows in one table that don’t appear in the other.

1

2

3

4

5

SELECT left_id

FROM left_table

MINUS

SELECT right_id

FROM right_table

Output:

| LEFT_ID |

|---|

| 2 |

| 3 |

The fields included in all the above operations must be of the same data type, since the results from both queries are stacked on top of each other in the final output.

Semi-joins & anti-joins

A semi-join returns rows from one table that have matching rows in another, but only shows columns from the first table.

1

2

3

4

SELECT left_id

FROM left_table

WHERE left_id IN (SELECT right_id

FROM right_table)

Output:

| LEFT_ID |

|---|

| 1 |

| 4 |

An anti-join does the opposite — it returns rows that don’t have a match.

1

2

3

4

SELECT left_id

FROM left_table

WHERE left_id NOT IN (SELECT right_id

FROM right_table)

Output:

| LEFT_ID |

|---|

| 2 |

| 3 |

These types of joins don’t have a dedicated SQL keyword like INNER or OUTER JOIN. Instead, they act as filtering mechanisms — limiting rows from one table based on the presence (or absence) of related rows in another.

Subqueries (nested queries)

A subquery (also known as an inner query or inner select) is a query nested inside another query. It can appear in the WHERE, SELECT, or FROM clause. The inner query runs first, and its result feeds into the outer one.

Subqueries don’t have a special syntax — they’re simply regular queries placed inside parentheses within a larger query (often called the outer query or outer select). The database executes the inner query first and then passes its result to the outer query. You can use comparison operators such as >, <, or = to compare this result with another expression.

Subquery inside WHERE clause

This is the most common use of a subquery — filtering rows in one table based on values calculated from another.

In the example below, the inner query finds the maximum left_id value from the left_table. The outer query then returns all rows from the right_table where right_id is greater than that maximum value.

1

2

3

4

SELECT *

FROM right_table

WHERE right_id > (SELECT MAX(left_id)

FROM left_table)

Output:

| RIGHT_ID | RIGHT_VAL |

|---|---|

| 5 | RIGHT 5 |

| 6 | RIGHT 6 |

Subquery inside SELECT clause

Here, the subquery acts like a calculated column. For each row in the outer query, the inner query runs once and produces a value that becomes part of the result set.

In this case, the inner query counts how many times each right_id appears in the left_table. The result is shown in a new column called left_id_count.

1

2

3

4

5

6

SELECT DISTINCT right_id,

(SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM left_table

WHERE left_table.left_id = right_table.right_id) AS

left_id_count

FROM right_table

Output:

| RIGHT_ID | LEFT_ID_COUNT |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 |

In other words: “For every row in the right table, count how many matching rows exist in the left table.”

Subquery inside FROM clause

When a subquery appears in the FROM clause, it behaves like a temporary table or derived dataset that the outer query can reference.

In this example, the inner query calculates the maximum left_id value from the left_table and labels it as left_max_id. The outer query then joins that single-row result to the right_table and retrieves any matching IDs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

SELECT right_table.right_id,

subquery1.left_max_id

FROM right_table,

(SELECT MAX(left_id) AS left_max_id

FROM left_table) subquery1

WHERE subquery1.left_max_id = right_table.right_id;

Output:

| RIGHT_ID | LEFT_MAX_ID |

|---|---|

| 4 | 4 |

Effectively: “Find the maximum ID in the left table, then show any rows from the right table that share that same ID.”

Quick summary

There are six primary SQL joins:

INNER JOIN(including self-joins)LEFT JOIN,RIGHT JOIN, andFULL OUTER JOINCROSS JOIN

You can also combine data using set operations (UNION, UNION ALL, INTERSECT, EXCEPT) and refine it with subqueries in the WHERE, SELECT, or FROM clause.

Conclusion

SQL joins are fundamental to working with relational data. They allow you to combine information from multiple tables to answer complex questions efficiently. Whether for analysis, reporting, or engineering, a solid grasp of join logic is essential in everyday data work.